http://www.instagram.com/sweetlabourartcollective/

The Sweet Labour Arts Collective was instigated by Kevin O’Connor, Ruth Douthwright, Billy Jack and keeps growing to include numerous guests artists (humans and more than humans).

Sweet Labour Art Collective

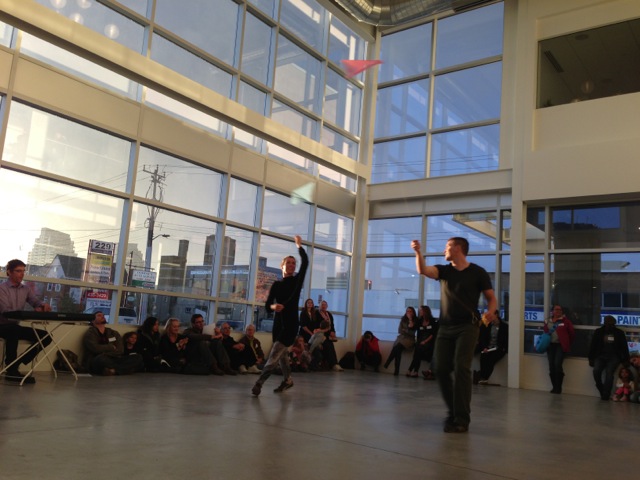

We are from London, Ontario, and the Oneida Nation of the Thames. This collective was instigated in 2010 by the late two-spirit multidisciplinary artist Billy Douthwright (Onkwehón:we) disability settler dance artist Ruth Douthwright, queer settler dance artist Kevin O’Connor (Gaelic/Sicilian). We now work with Marshall Stonefish (Oneida, Chippewa filmmaker/ editor), two-spirit Multidisciplinary Artist/dancer/choreographer Montana Summers (Onkwehón:we), two-spirit Oneida language keeper Brooke Chrisjohn, settler multidisciplinary artist Linda Jantz, and numerous other guest artists and community members. We came together through complex world-making practices that include adoption, immigration, the forced removal of the Oneida people from their territory in what is today called New York State, settler colonial practices, performance events in North America, and travel between Oneida Nation of the Thames and the Soho neighbourhood in London Ontario. We have instigated multiple community-engaged multi-arts projects. Our collective works within the friction and paradoxes of the colonial relations that brought us all together. We make performance work that intersects film, site-based dance performance, audience participation, contemporary folk, Indigenous dance practices, and audience participatory scores. We have produced films, sold out live performances, made zines, and facilitated workshops for the broader public in London and internationally.

BIOS:

Ruth Douthwright (choreographer, dancer, curator) I am a multidisciplinary artist, educator, and mother living in London, ON where I create with Sweet Labour Art Collective. I develop curriculum and deliver programming in multiple communities for people with a wide range of physical and intellectual abilities and disabilities – The Art of Remembering at McCormick, Togethering with L’Arche and PH House, Recovery Through the Arts at Parkwood Mental Health and Museum School at Museum London. From 2020-2023 I was a collaborating artist with The Sense Archive. I am currently developing programming in mindful movement and somatic practices with a special focus on support for breast cancer patients based on my personal process and ongoing rehabilitation.

Kevin O’Connor (choreographer, dancer, writer, producer) (he/him/they) I am a multidisciplinary artist of Gaelic and Sicilian descent, and my work is deeply rooted in collaboration, community-engaged arts, somatics, ecology, and queer activism. For the past fifteen years, I have been an integral member of Sweet Labour Arts, based in London, Ontario. Additionally, I have had the privilege of collaborating with various remarkable artists and collectives, including NAKA Dance, Oakland, Oncogrrrls feminist collective, Spain, Anandam, Toronto, and a collaboration with Inuit hunter Paulette Metuq on a project in Nunavut. Over the past two years, I’ve embarked on collaborations for two distinct experimental dance projects: TRY (San Francisco/New York City) and All the Rage (Guelph/Toronto). I hold a degree in ecology from UBC, a diploma from the National Circus School of Montreal, an MFA in choreography, and a Ph.D. in performance studies from UC Davis. www.ecologicalbodying.com.

Brooke Chrisjohn: Shekoli swakweku, Brooke ni’yukyats, Othayu:ni niwaki’talo:t^, Onyota’a:ka niwakuhutsyo:t^. My name is Brooke Chrisjohn, I am from the wolf clan and from ONEIDA NATION OF THE THAMES. I am a dedicated mother to five beautiful children, loving partner, and Oneida language lifelong learner/teacher. I have had the honour to work with this team of beautiful people at Sweet Labour Art Collective, this has been a great learning opportunity along the way. Yaw^ko. Past projects are: Compost – Recomposing Relations, November 2022, Choreographies of Care, Winter 2022 and most recently workshops with daycare workers, March 2023.

Marshall Stonefish is an Oneida Nation of the Thames filmmaker, editor, photographer and director. He is self-taught in filmmaking and studied photography at Fanshawe which kickstarted both his photography and film career. From 2020-2022 he collaborated with numerous Southwestern Ontario dance artists working on dance film projects. These credits include: collaborating with Sweet Labour Art for their Canada Council of the Arts sponsored film project called Compost: Recomposing Relations; for Public Displays of Art’s project called Augmented Spaces; and, on a dance film collaboration with Montana Summers for Sante Smith’s Kaha:wi Dance Theatre’s curated video performances platform Call and Response to Spring (co-presented by Woodland Cultural Center). He is also a film editor and music composer.

Montana Summers is from the Oneida First Nation of the Thames. Montana began training in the exploration of Indigenous and contemporary dance when he was accepted into the Indigenous Dance Residency (2015) and Kaha:wi Dance Theatre’s Summer Intensive (2016). Kaha:wi Dance Theatre’s Artistic Director, Santee Smith, brought Montana onto projects including The Mush Hole (2016-2020), I Lost My Talk with the National Arts Centre Orchestra (2016) and for the Grand Act of Theatre, Continuance: Yonkwa’nikonhrakontàhkwen–Our Consciousness Continues Unchanged (2020), and The Honouring. Additionally, Montana previously acted for Backyard Theatre’s one-time new production called The Other Side of the River (2019). Montana continues to work on his abilities in the performing arts with other small projects from Kaha:wi Dance Theatre, multiple collectives he is a part of in London, including the Sweet Labour Art Collective, and other colleagues. Montana hopes to inspire youth among his community to chase their dreams.

We are from London, Ontario, and the Oneida Nation of the Thames. The collective was instigated by Ruth and Kevin, and Billy. We came together through complex world-making practices that include adoption, immigration, the forced removal of the Oneida people from their territory, settler colonial killing practices, dance events in London, migrating relations between the Oneida of the Thames and the Soho neighbourhood of London Ontario.

This collective keeps growing as we continue to work with many artists who live and work alongside the D’eshkinzibi river. We are dancers, visual artists, language keepers, media makers, costume artists, actors, improvisers, writers, ceramic artists and musicians. We also work with teachers, nurses, doctors, care workers, and trades folk. This collective is a complex we, coming from different places, with different sense-abilities and different ways of worlding. In being a complex we, the presences in this collective that interact acknowledge the mutual excesses, sometimes incommensurable, that are part of the relating. We embrace the uncommon ground and the friction and creative returns of the excesses that escape knowing, which are part of our group’s togethering practices.

Our work started out by thinking through multiple forms of ecological knowing, playing with queering boundaries between humans and other than humans, including toxic landscapes such as the Deshkan Ziibi (renamed the Thames River), that runs through the neighbourhood where we live and make work. Our collective has always worked within the friction and paradoxes of the colonial relations that brought us all together.

We are interested in how improvisation scores can be a method for inviting diverse publics into a rehearsal or performance as a mode of thinking together across differences. Rehearsals allow us to find an interest in common to continue to work together without complying to sameness. We think of rehearsals as practices of infrastructure-ing new possible worlds into being. Currently, we are also working on researching the intersection of improvisation and practices of care across different worlds within institutional caregiving settings.

Our collective has always worked within the friction and paradoxes of the colonial relations that brought us all together. As a group we have received grants from the London Arts Council, Madawaska Valley Arts Council, Ontario Arts Council and Canada Council for the Arts. We use contemporary dance methods including dance improvisation, folkloric dances, Indigenous contemporary (Oneida nation) dance, aerial dance, somatic practices, film making, storytelling and participatory methods such as group improvisation open-ended scores.

.

Some questions that guide us:

How can we experiment with sensory practices that allow for experiences of being together that can disrupt dominant forms of ecological knowing? How might we engage with polluted landscapes? What and whose stories have been erased? What do we learn from the Indigenous people’s relationship to these places over time, into the present and future? How can we engage speculatively with tendencies or practices that could be making new sense-able worlds?

We grew up walking the streets and trails along the polluted river every day. We often rehearsed in the playground in the park by the river. There is a bouncy rubber tire floor that we could move on while Ruth’s kids played. We were constantly trying to figure out how to rehearse and plan with the kids around. Ruth could not afford to have daycare all the time. We work with an audience as the medium for the performance work and so having kids in the rehearsal helped us think with scores that would include children and help us learn from their particular attentional practices.

Our art-making collective has led collaborative art-making processes where we examine a particular community’s relation to the watershed they live in though site based participatory performance. In focusing on the relation in our art-making practices we have experimented and developed different open-ended scores. These scores are kinds of propositions for new kinds of relations to emerge. Within these scores, each audience member enters into a relation or cultivates one with both humans and other than humans, unique to the site. This coming into relation and the potential for making differences is what makes the grounds for these performances to come together. The basis for the performance is gifting as each audience member gives something to the particular event unfolding they are in relation to, without knowing or demanding if or how or when the gift will be returned. We question how performance practices can foreground ways we are ‘shaping and being shaped” by the human and other than human entities and forces that live amongst us, unique to each site.

Oneida Naming

It is the Oneida naming of river that runs through our neighborhood that helped me think through the art making practices we as a collective try to engage in. The Oneida did not rename the river when they were forced to settled by it in Ontario in the 1800s. They simply refer to the Kuayuhatati or along the river (Mulcahy 2008). This practice of not renaming, and creating alongside other names and stories, inspires our own critical art making practices. The etymological strand in the OED (2013) relates alongside to being close by the side of a person or thing; side by side with something; parallel to something. Alongside also can mean together with; at the same time as; in coexistence with. Alongside work recognizes hegemonic discourse, inflected by the hegemonic system in which it is situated, yet knows its own practices have value and agency (Hunter 2014). In working alongside hegemonic structure we work from a need to embody other kinds of ways being in relation to the land we live on, outside of those ways the nation state conceives of.

Ruth, Billy and Kevin grew up in the neighbourhood called SoHo (South of Horton) in London Ontario. SoHo has existed within the same boundaries since London’s inception in 1840. Originally named St. David’s Ward, this neighbourhood is bordered on the north by the CN railroad tracks parallel to, and north of Horton St., on the east by Adelaide St., and on the south and west by the Thames River, originally called The Antler River or Deshkan Ziibiing in Chippewayan, the aboriginal history stretching back for at least eleven millennia. Its 150-year colonial history includes its early days as a place of refuge on the Underground Railroad, to housing one of the City’s major medical facilities, to being located along the edges of the downtown and the Thames River. These factors have given this neighbourhood a prominent role in the development of the City.

Kevin is a mix of Irish, Scottish, Sicilian immigrants who moved to London in the late 18th century. Ruth, a choreographer and dancer was born in London. Her mother immigrated to Canada to the United Kingdom in her twenties and was our first dance and improvisation teacher. Billy, a visual artist, was born on the Onyota’a:kA (Oneida) reserve near London and adopted by Ruth’s family. Before European contact, the Oneida territory included most of New York State. In 1838, the Treaty of Buffalo Creek directed the removal of all Iroquois from New York State. The Oneidas sold their New York land in 1839 and jointly purchased 5,200 acres near London, Ontario (Hauptman et al. 1999). Our art-making collective’s coming together is fraught with contradictions. Preceded and inevitably coloured by colonial settler displacement and killing practices, our art making collaboration, shapes, challenges and continuously makes us different.